Queen Creek resident Elvis Bray, a Vietnam War veteran, has spent his retirement years helping other veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) through writing about their experiences.

“Helping veterans with PTSD is the only real important writing I do,” Bray said. “I consider it ‘God's work’ knowing I made a difference in someone's life. It’s very important to me.”

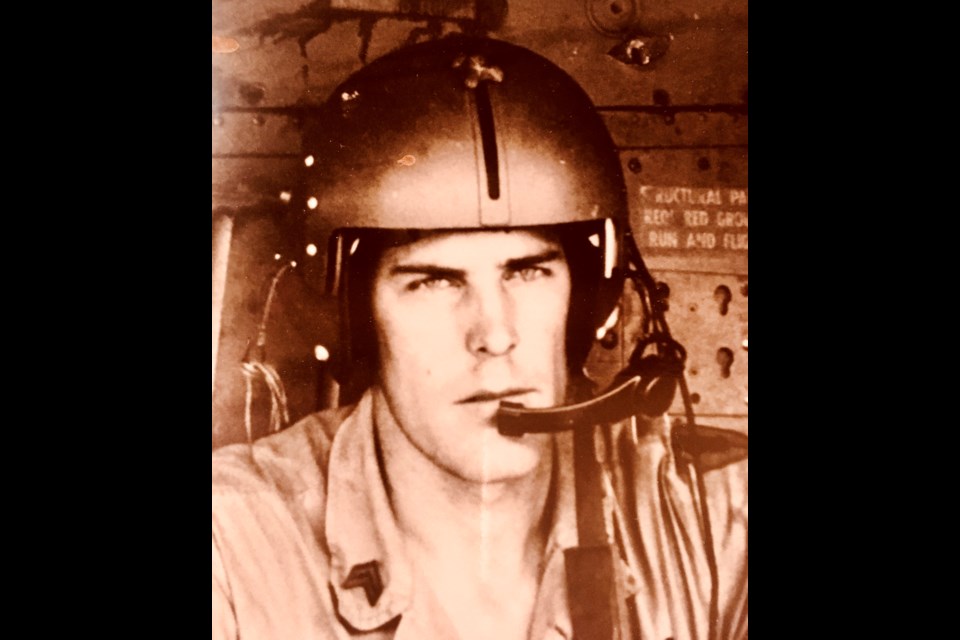

Bray was an E-5 enlisted U.S. Army crew chief who did a tour in Vietnam in 1968 and '69 with the 7th/1st Air Cav in Vinh Long doing search and destroy missions.

"I volunteered to stay for a second tour (1969-1970) and flew as a crew chief for the Dustoff (Medevac) in the central highlands," he said. "I was shot down four times and have a purple heart. I'm not a hero, but I served with many."

Now retired from serving 35 years in Arizona law enforcement, Bray writes books as a hobby and helps veterans with PTSD write their stories.

"Some veterans keep things inside themselves for years, never telling anyone, or just a few friends," Bray said. "It eats away at them like cancer until they start having nightmares or maybe turning to alcohol or drugs to numb the pain. Writing their stories gives them a way to express what they did and how they feel. Each veteran's story is unique and different."

Bray continued: "Ben Bentley will tell you that by me writing his story helped lift the weight of the world off his shoulders. He now has a way to tell his story to friends and family that he could not tell for over 50 years. Jerry Free will tell you that writing his story freed him from misinformation he had not known because he was unconscious and woke up burning. He never returned to his home base and didn't know the facts. He never knew what many good men did to help save his life. John McCarney will tell you he was almost ashamed to admit that he served in the military until I helped him verbally and then helped him write his story. He is now a proud veteran, no longer feeling unworthy and helps other veterans. Some veteran stories are too painful for them to tell. It is like unlocking Pandora's box. I can't help them."

The veteran turned author grew up in the East Valley.

“My parents moved to Mesa from Chandler in 1958. I lived in Mesa until I moved to Queen Creek 11 years ago,” Bray said. "I turned 20 and 21 in Vietnam. I wasn't old enough to drink alcohol or vote until I turned 21."

Bray retired from the Mesa Police Department after 20 years of service before going on to serve as a police officer with Mesa Community College. After 15 years at MCC, Bray retired after being the first police officer to be hired at MCC.

As an American author specializing in crime, suspense fiction and war novels, Bray has published three books: "The Presence of Justice," "Dual Therapy" and "The Presence of Conflict." "The Presence of Justice" was a finalist in the Arizona Authors' Association's 2016 Book of the Year and "Dual Therapy" was a finalist in the 2017 Book of the Year.

Bray has completed a first screenplay from his book, "Dual Therapy," that received a recommendation from Extreme Screenwriters of LA and was the featured screenplay of the month in June 2019 in their monthly newsletter.

He lives in Queen Creek with his wife, three horses, two dogs and one cat. He is working on a sequel to "Dual Therapy" called, "The Raven and the Dove."

Bray wrote the following for Veterans Day:

Real Soldiers Don’t Cry

Elvis Bray

The jungles below looked inviting from a thousand feet in the air. But that was an illusion. Tigers, cobras, bamboo vipers and the Viet Cong made them a dangerous place to venture. We were somewhere between Saigon and Cam Ronh Bay in the Central Highlands of South Vietnam in 1969. A wounded American soldier was down there somewhere and it was our job to go get him out.

So much blood covered the floor of our UH-1H Dustoff Helicopter that my boots were sticking to it. I’d lost count of how many extractions we’d made that day. Hopefully this would be our last. We hadn’t shut the engine down in the last sixteen hours and I could barely keep my eyes open. I wondered how the pilots were able to keep flying.

The river below ran westward in a deep valley. It was the only river I had ever seen in Vietnam with clear water. All the rest were a murky brown color and smelled like sewage.

The sun had already set in the western sky. We wanted to evacuate quickly before it was too dark to see. Spotting smoke on the south bank of the river, the pilot confirmed the smoke thrown was yellow. The jungle was so thick we couldn’t see the ground. The only place to put the helicopter down was in the river. We couldn’t tell how deep the swift water was. Soldiers lay in the prone position on the bank pointing their rifles toward the opposite side of the river in case we started taking fire.

The pilot pointed the nose upstream and put the skids in the water. He maneuvered the helicopter as close to the bank as possible without the rotor blades hitting the overhanging trees. Several men carried a stretcher out to the water's edge. Other troops locked arms, forming a human chain and started wading out into the swift water. It took about a dozen men to reach the helicopter. The first guy to reach us wrapped his arm around the skid to keep from being washed away. The pilot struggled to keep the helicopter steady in the current as the belly of the chopper slowly filled with water.

Four men lifted the stretcher onto their shoulders and waded into the swift current. The only thing keeping them from being washed downstream was the human chain of men already in the cold water. They had to be careful to keep from slipping on the rocks and dumping the patient into the river. Harvey and I grabbed the stretcher as soon as we could reach it. If we lifted it too high, the wounded soldier would slide off the back of the litter. The pilot lowered the helicopter deeper into the river and we pulled him safely inside.

As soon as we had our patient secured, another soldier was brought to the helicopter. Two soldiers held him by his arms and walked him into the water. I couldn’t see any wounds or blood on him but he looked like he could hardly stand up. When he got to the helicopter, they helped him inside the jump seat on the side of the chopper. This is where we put patients with minor injuries so they wouldn’t be in our way while we’re treating the seriously wounded.

When the second soldier was secure, I shut the door and we lifted out of the water. The pilot hovered for a few moments letting the water drain out of the bottom of the helicopter. It was almost completely dark by the time we were airborne.

As we rose into the night sky, I felt sorry for the soldiers we left behind. They would have a very cold night ahead of them. As soon as we gained altitude, the medic turned on the overhead red light so he could treat our patients.

One look and we both knew the man at our feet was already dead. He had a small hole in the center of his forehead and there was brain matter on the litter behind him. Harvey spoke into the intercom. “This guy’s dead and has been dead for a long time.”

The pilot glanced back at us. “Why in the heck would they have us risk our lives for a dead guy?”

“I know, Sir. He’s shot right between the eyes and died instantly,” Harvey said.

The pilot shook his head and turned back towards the front of the cockpit.

Harvey looked at me. “See what’s wrong with the other guy.”

I went to the side compartment to check on him. He was staring straight out into the darkness. “Are you all right?” I yelled.

He didn’t answer me. I yelled a little louder, “Hey buddy, are you okay?” He still didn’t answer me. I moved closer and reached out and touched his arm. He jerked his head around and stared straight through me. It was the strangest look I had ever seen in anyone’s eyes. Dark, blank, cold and empty. He just stared at me as if he were looking right into my soul. We stared at each other for a few moments. I asked again, “Are you wounded?” He held the stare for a few more moments and then slowly shook his head no. He never blinked. Turning his head, he stared into the darkness.

I moved back into the center area of the helicopter. “He’s not wounded.”

Harvey scooted over to the center of the helicopter and looked back at the guy and then at me. “What's going on here? We risk our butts for a dead man and some jerk that’s not even wounded.”

Harvey was right. It didn’t make sense. We would never risk four men and a helicopter to evacuate a dead man. We would normally wait until we had a secured landing zone. The pilot and co-pilot glanced back at us. Everyone was pissed.

I studied the face of the dead soldier for a long time. He looked to be about nineteen years old and in good shape. He could easily have been one of my football teammates. The small round hole in his forehead and the scrambled eggs on the litter next to him was the only sign of injury. It looked as if he were sleeping peacefully. Keeling down, I closed his eyes.

His family was going about their daily business unaware that their son or brother or husband had been killed. I wondered how long it would take before someone showed up on their front porch with the bad news. I felt sorry for them whoever they were. A recurring thought crept into my mind. I had thought of it many times during the year and a half I’d spent in Vietnam. Once again blood stained these eyes of war. I was tired and saddened.

The guy sitting in the jump seat hadn’t moved. He just sat there staring out into the night. He too was about my age and he could have been one of my football teammates as well. I couldn’t help wondering what the heck he was doing in my helicopter. Anger swelled up inside me. For a moment, I thought about going back there and throwing his butt out. But we didn’t do those things. The more I thought about him the madder I got. I couldn’t believe we had risked our helicopter and our lives for that guy. I was too tired to think about him any longer. I laid back and closed my eyes.

We landed at the field hospital at Camp Betty on the outskirts of Phan Theit. Doctors and nurses rushed out to unload the patients. We slid the litter towards them. They grabbed it and carried the dead man away. The black guy in the jump seat just sat there. A nurse offered him her hand but he didn’t act as if he even saw her. I started moving to get off to throw him out. By the time I got there, a doctor had grabbed his arm and was helping him down. The last I saw of the soldier, he was being guided into the hospital. I spat on the ground and closed the door.

After fueling the helicopter, we flew to our landing pad and the pilot shut the helicopter down. As soon as I had the blades tied, I went to my bunk. The rest of the crew was already asleep. We were too tired to eat.

It was mid-morning before I awoke. I still had blood on my clothes and boots. Thankful we hadn’t been called out again last night. I’d never been so tired in my life. I went to the mess hall, grabbed some breakfast and drank a gallon of coffee.

Sufficiently caffeinated, I went to the helicopter where Harvey was pouring bottles of hydrogen peroxide on the floor of the helicopter. Six inches of pink foam leaked out of the chopper. “Can you believe it, Bray?”

I shook my head. “We’ve never had that much blood before. I’m going to have to pull the panels and clean them.”

“No kidding.”

I retrieved several buckets of water and flushed the foam out of the helicopter. A pink river ran off the landing pad onto the dirt and down the flight line. Harvey went to the hospital to get more medical supplies.

I checked the helicopter and found a small hole in the tail-boom and another one in the rotor blade. I hadn’t even known we’d been hit.

When Harvey returned, I told him about the bullet holes. He didn’t act surprised, or concerned.

“Did you ever find out what was wrong with that black guy we brought in last night? I asked.

“No. Probably had jungle rot or something. I didn’t see anything wrong with him.”

We were still upset from the night before. “They already knew the other guy was dead before they called us in.”

“Yeah, that was nonsense.”

“I’m going to the hospital and find out why we risked our lives for that guy.”

“I’ll go with you,” I said.

“He better have a good reason for being here.”

We were both hot, tired and bent on looking for answers. We checked the infirmary and couldn’t find the guy. We went into the emergency room. The doctor who had helped the guy off the chopper was just finishing wrapping up some guy’s foot.

“Hey Doc. What was the deal with that last guy we brought in last night?” I asked.

“Which guy are you talking about?”

“That black guy who came in with the dead guy on our last load.” “The guy without any injuries,” Harvey said.

I could tell by the expression on the Doc’s face, he didn’t appreciate our comments. He poured himself a cup of coffee. “He was wounded alright. You just couldn’t see the wounds.”

“What are you talking about, Doc? He didn’t have a scratch on him,” Harvey said.

The doctor took a deep breath. “The two guys you brought in last night were best friends from high school. They played football together. When the white guy got his draft notice, his friend joined up with him on the buddy plan so they could look after one another.”

Doc rubbed his chin and took a drink. “Those men had been out in the field for three weeks. They camped by the river last night so no one could sneak up behind them. They’d dug their foxholes and were trying to get a bite to eat when they started taking sniper fire. They both ran to their foxhole and jumped in. When they landed, the black guy’s M-16 discharged hitting his buddy in the forehead. They were only a foot apart at the time.”

It took a few moments for the information to sink in. “So, he was in shock,” said Harvey. Shaking his head, he walked away without saying another word.

“Where is he, Doc?” I asked.

“He tried to kill himself last night. I sedated him and we shipped him out this morning. He’s on suicide watch.”

I now knew why they had called us in. It wasn’t for the dead guy but for his best friend. We just couldn’t see the injuries to his soul. I felt terrible for misjudging the man and the situation. “Once again blood stained these eyes of war.”

“What?” The Doctor asked.

“Oh, nothing, Doc.” I walked away, forcing back tears. Real soldiers don’t cry.